- Web Desk

- 38 Minutes ago

I write love stories, and love stories are always relevant: Mohammed Hanif on ‘Rebel English Academy’

-

- Zoya Anwer

- Feb 12, 2026

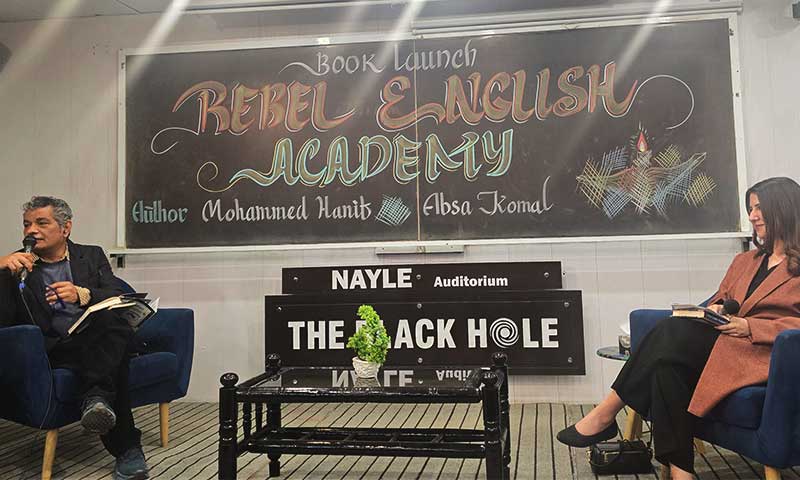

A rainy evening in Islamabad would usually mean a low turnout at an event, especially a literary one, but the premises of Blackhole were filled to the brim even before author Mohammed Hanif arrived at the venue. Hosted by journalist Absa Komal, the event welcomed Hanif’s recent novel Rebel English Academy, which was launched earlier this month.

Hanif, who was coming to Islamabad after a decade, spoke about his work, which begins with the night of the hanging of former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Speaking about the opening, Hanif said that he went back to his memories as a teenager when he was supposed to rote-learn his way through exams in the hope that life would change for the better — but it didn’t.

“Looking back, I remember that day when the streets were deserted, what we call hoo ka alam. There was a lot of fear alongside some excitement, but suspicion was the dominant feeling. There was no social media, so there was wide speculation. But again, as a student who had just gotten done with an exam, I could not care less. I did not know what happened in Islamabad then, and don’t know to this date,” he quipped.

The characters in Rebel English Academy

Returning to the characters in the book, Hanif spoke about Captain Gul and Baaghi, with the former being what can be dubbed a ‘lover boy’. Full of hope and looking forward to the joys of life, Captain Gul has been stationed in OK Town from Rawalpindi to reap what he had sown. Baaghi, on the other hand, is a rebel who is perhaps trying to find meaning again against the backdrop of the hanging, and so he begins an English academy to teach the underserved English.

“You all are sitting here because you can read a sentence or two in English, after all. The thing is that, like disillusioned revolutionaries open up NGOs in Islamabad, Baaghi opened an English academy. He is principled and honourable and wishes to change society,” Hanif explained taking a moment to remember the late Sabeen Mahmud, who was shot dead in Karachi in 2015.

Joking about the struggles with language, Hanif spoke about public schools in Punjab where, at first, Urdu is taught in Punjabi and then English is taught in Urdu, leaving students confused about the language spoken at home versus school.

Another character discussed was Sabeeha, who is an athlete and a fugitive, enrolled at the academy and performs well by ensuring that her essays are filled with difficult English words to impress the teacher. “It was challenging to write her character because you are writing in the voice of a young girl as a middle-aged man.”

Referring to a letter about ‘Our Cow’, which Sabeeha writes, Hanif recalled that in non-urban spaces, transferring a cow from one place to another is a big deal, and letters are often written explaining the necessity behind the act.

Satire, love, and channeling madness

Speaking about satire, Hanif said he felt that making fun of oneself is the most difficult, but it is not as hard when it comes to other beings or structures. Commenting on the relevancy of the text in current times, he said that love stories are timeless: “I write love stories and love stories are always relevant. You have to channel your madness into a novel, not current affairs.”

“But it is getting redundant because, looking around at how ridiculous things are, there isn’t a need to make fun of them anymore. Plus, nobody really cares. We like to think they do, but they are indifferent. I write about Captains because there is so much to explore,” he said, adding that senior ranks are quite boring to write about because they have already done everything, leaving hardly anything to be written about.

When asked about the translation of A Case of Exploding Mangoes into Urdu, which led to the disappearance of copies, Hanif responded with another quip: “In a country where citizens vanish and go missing, it is self-indulgent to be concerned about missing books.”

He also clarified that, contrary to the popular belief that people read more in Urdu than in English, people just do not read anymore.

When asked whether the opening scene could in any way insinuate another former prime minister behind bars, Hanif said that when he started writing the book, he had just become the prime minister, adding that when it comes to being behind bars, there are many men and women who have been imprisoned.

“A woman came to this city asking about her father, and now she is in jail. Then another woman spoke for that woman, and now she is also behind bars,” he said, referring to BYC leader Mahrang Baloch and human rights lawyer Imaan Mazari.