- Web Desk

- 11 Minutes ago

No bloodshed, no big clashes: how reporters experienced Bangladesh’s 2026 Election

-

- Zoya Anwer

- Feb 17, 2026

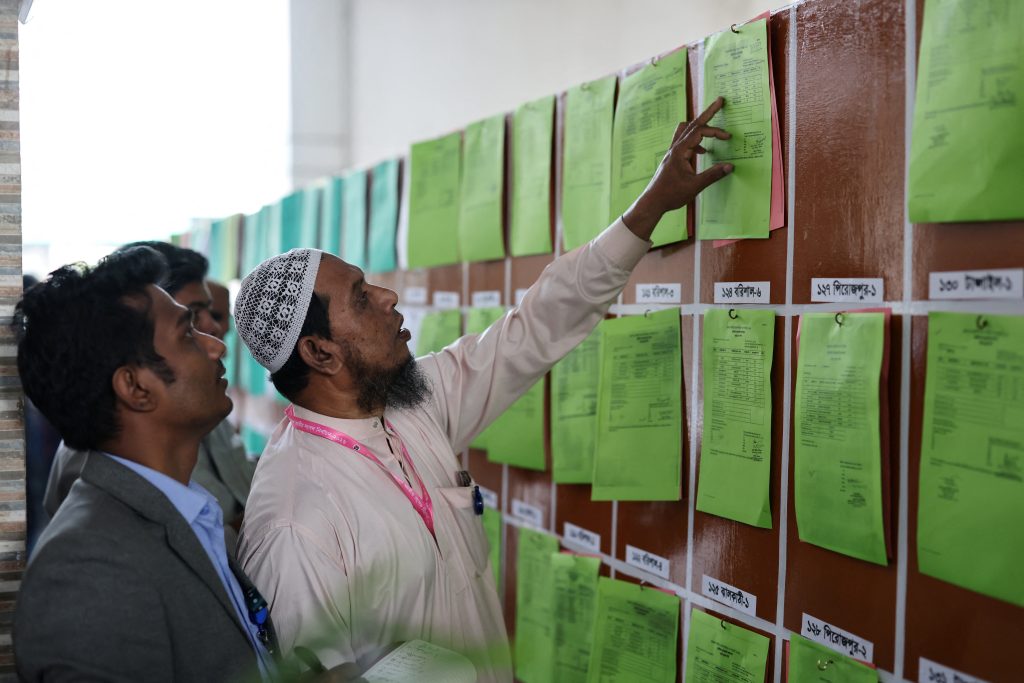

When Bangladesh went to the polls on February 12, 2026, it was not just voters who carried the weight of history, journalists did too. Tasked with documenting the first general election since the Gen Z-led uprising that ousted Sheikh Hasina, reporters fanned out across cities and rural constituencies, bracing for unrest. What many of them witnessed instead was a vote strikingly calmer than those of the past.

The centre-right Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) secured a landslide majority, taking more than two-thirds of parliamentary seats. With the Awami League barred from contesting and Jamaat emerging as the second-largest bloc, the political order shifted dramatically. BNP chairman Tarique Rahman, has been sworn in as prime minister, promising to restore democracy after 15 years of authoritarian rule, telling supporters, “I am grateful for the love you have shown me,” while urging restraint rather than celebration.

But beyond the numbers and speeches, it was the atmosphere on the ground that left seasoned reporters reassessing their expectations.

“Comparatively better and more peaceful”

Associated with Ekhon TV, senior reporter Faisal Karim, who has covered three previous national elections, approached polling day in Chittagong with caution. Historically, elections in Bangladesh have often been marred by violence and allegations of rigging.

“In the days before the vote, we expected incidents,” he said, recalling the anxiety among media workers. “We were actually a bit worried about what would happen.”

Instead, the reality surprised him.

“This election is better in the sense that there’s no bloodshed, no big incidents, no murder,” Karim said. Reports of “vote rigging, forceful voting, or stuffing the ballots”, once routine, were largely absent in his coverage area.

He did not portray the process as flawless. There were “some events of forceful voting, or buying the vote,” he acknowledged, but stressed that these were isolated and not widespread.

Even while reporting from rural constituencies he described as “risky zones,” Karim said he felt secure. “I didn’t feel any threats from any party members or any candidate’s representative.” He attributed the relative calm to the “significant” and “strict role” of law enforcement agencies, particularly the army, which he said “ensured that the vote is going free and fair.”

A festival before sunrise

Mahfuz Mishu’s day began before dawn. Polling was set to open at 7:30am, but in some centres voters were already lined up by 6:30am.

“It was like a festival,” he said. “A big festival among the mass people.”

Associated with Jamuna Television as Special Correspondent, Mishu noticed two groups in particular.

Young voters, aged 18 to 35, turned out in large numbers, many casting ballots for the first time. He explained that the previous three elections had been widely criticised as flawed, leaving this generation without what they felt was a meaningful opportunity to vote.

“They were like, ‘I have never voted, so I have to cast my vote as early as possible,’” he said.

Older citizens, aged roughly 55 to 75, were also highly visible. In Mishu’s assessment, many believed this might be their final chance to participate in shaping the nation’s future.

Official turnout stood at 59.44%, according to the Election Commission. Mishu suggested participation might have been higher had all major parties, particularly the Awami League, been allowed to contest. Still, he described the atmosphere as largely free and open.

“This is the first election so far I know without having any death or any big clash around the country,” he said.

Reporting without fear

For both journalists, the absence of violence was matched by something equally significant: professional freedom.

Mishu noted that in past elections, journalists often faced implicit or explicit pressure. This time, he said, reporters worked largely without “special direction” from authorities.

Karim echoed that sentiment, emphasising that he did not feel threatened by party activists or candidates’ representatives, a notable departure from previous election cycles.

Though tensions simmered in the lead-up to polling, Mishu described the eve of the vote as potentially “very risky”, those fears did not materialise into widespread unrest.

“It will be a good memory in our career,” he reflected.

A mandate and a test

With the BNP securing a commanding majority and voters endorsing sweeping democratic reforms in a parallel referendum, the political transition now moves from ballot boxes to governance.

Rahman, who spent 17 years in self-imposed exile before returning to Bangladesh shortly before his mother Khaleda Zia’s death, faces immense challenges: reviving a fragile economy, controlling rising food prices, creating jobs for a vast youth population, and repairing strained ties with India.

The absence of Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia — two figures who dominated Bangladeshi politics for decades, marks a symbolic turning point. Yet as the country looks ahead, journalists who bore witness to the day’s events remain cautiously reflective.

After years of turbulent and contested elections, February 12, 2026, stood out not only for its political consequences but for its relative calm.

For the reporters on the ground, that calm was not just news, rather it was history unfolding in real time.